Translation: Rich Brown

Photography: Melissa Miranda

Two enormous mango trees offer shade on the muddy patio of the home of Jasmin Tomás. This is perhaps the best season for their mangos, which have just ripened and sometimes fall to the ground. Some sink into the mud before Jasmin and her family devour them.

Jasmin is 11. She doesn’t draw. What she likes, despite her age and her diminutive height, is to ride her mom’s moped. Without asking permission, she’ll start it up and head to the store to buy ice cream, candy, or school supplies, or run some other errand, any excuse to ride through the hamlet of La Democracia. Upon return, she climbs the steep cobblestone slope to her home and parks the scooter under the simple colonnade that shades the patio.

Her dad, Marco Antonio Tomás, left ten years ago because he couldn’t find work that paid enough to maintain his family. Ever since, the family has been divided by 1,900 miles and a border wall guarded day and night.

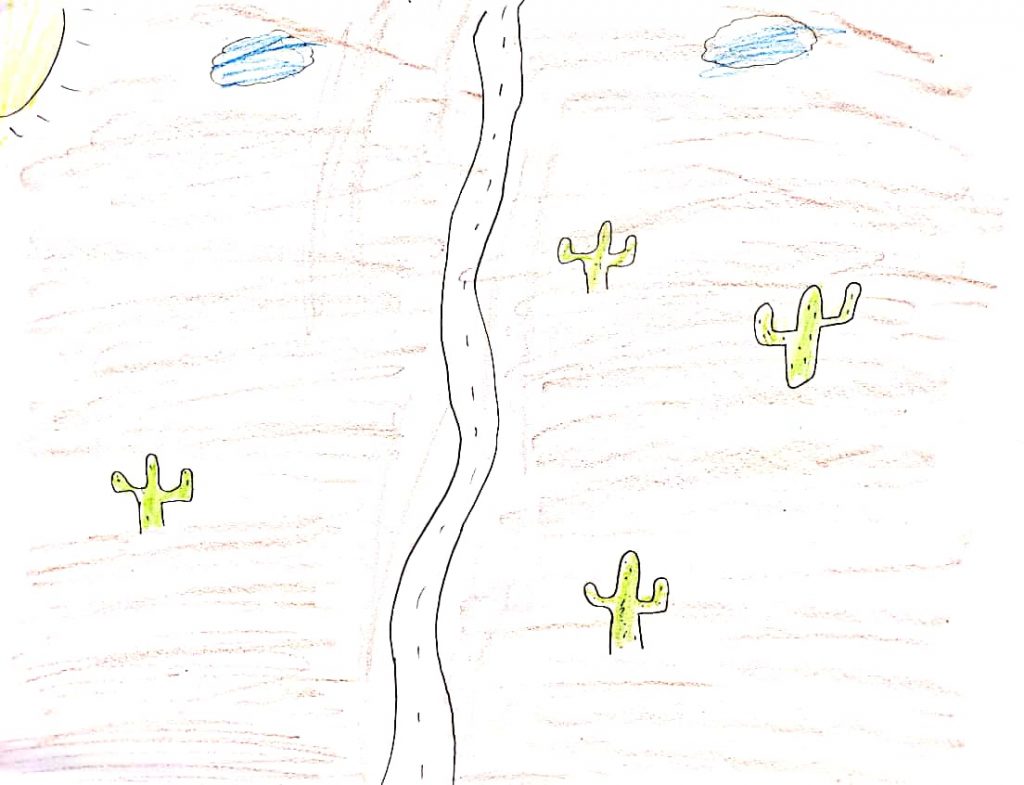

In Malacatán, Jasmin lives with her two brothers and her mother. The youngest and most restless is Justin. He’s 9 years old, nicknamed “Toti.” The eldest is Brandon, but everyone calls him “Chino” for how his eyes look when he smiles. He’s 15, with an indisputable talent for pencil drawing and, recently, a lack of interest in school. A couple of months ago he decided to drop out. His mother, Rosa Bámaca, is a pleasant, cheerful 35-year-old woman. She pled with him to stay in school, but to no avail.

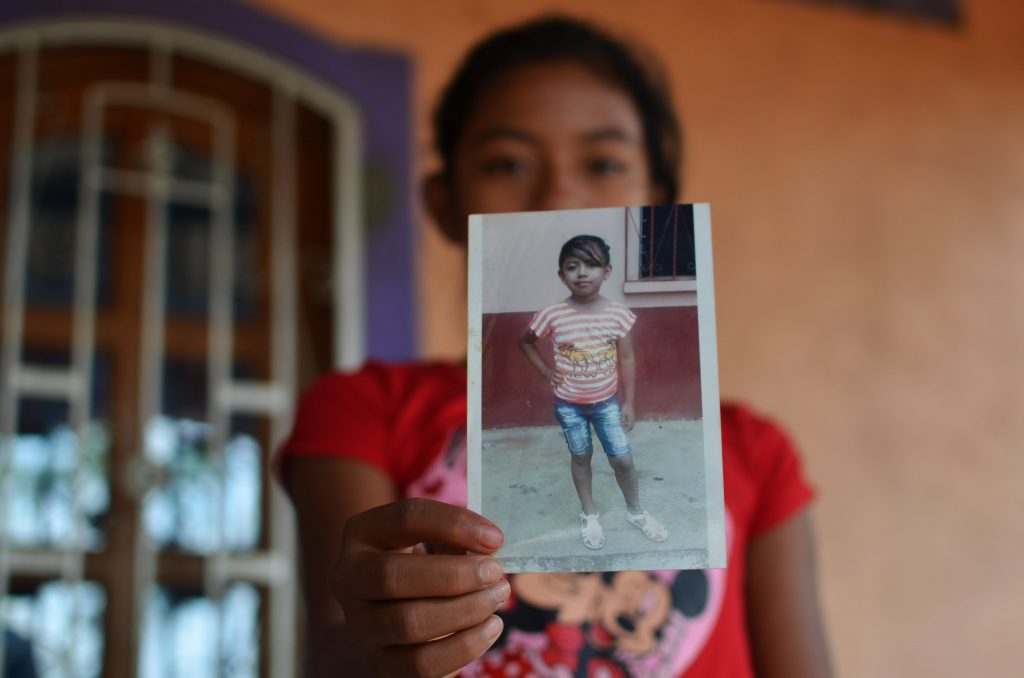

The first time Marco Antonio left for the US, Brandon was three months old. He saw Brandon again two years later after he was deported. It was a short stay, under three years, but during this time, Jasmin joined the family. None of the kids have memories with their dad. All they know of him has come through their video-calls.

New technology lessens heartache, but it hasn’t prevented Jasmin from feeling that her dad is a figure far removed to her days in La Democracia. She doesn’t know how he makes a living, what the house where he lives is like, who he lives with, how New York State is, or what the roads he travels every day are like. She has only vague notions. She says her dad works taking care of cows. Toti is a little more specific. He thinks his dad milks the cows. Rosa, meanwhile, clarifies that he works on a cattle ranch.

Yasmin, Toti, and Brandon picture the US as very different from Malacatán. Like the weather, for example. There, it snows, and “the water is really cold,” Toti says. To compensate, the houses are very big, with three floors, much bigger than theirs. All these images are built thanks to conversations with their dad, what they’ve seen on TV, and a few photos of Marco Antonio standing in the snow.

Despite the landscape, which looks nice to them, the siblings say that here in Guatemala they’re more free than they could be in the US. Here, they say, they can go out without worrying, visiting their aunts and uncles and cousins or taking their mom’s moped for a spin. “There you can’t have animals,” Toti says. Jasmin quickly agrees.

None of them likes the idea of leaving behind their home, their three cows, their eight dogs, their mango, avocado and lime trees, or their mother to go to the US.

But Brandon isn’t sure. He was a top student in high school, but a few months ago he lost interest in school because he didn’t like the virtual learning imposed by the pandemic. Now he wants to enter an academy to become a soccer player.

Jasmin’s in fifth grade, and wants to become a doctor. Toti’s in second, and wants to be a mechanic or work with livestock like his dad. He’s a fanatic for Animal Planet, the cable channel he watches as soon as he finishes the chores Rosa assigns him.

Justin and Toti never lack entertainment. If it doesn’t come from one of their three TVs, it’s with the animals, the moped, the large front patio with the mango trees, the house next door where their aunts live, or the tilapia Rosa is trying to raise in the four small concrete basins Marco sent money to build. Jasmin says she’s happy.

Every two weeks, Marco Antonio sends money. Some for Rosa and some for his dad, Rosa’s father-in-law, who manages spending for their home improvement projects. The family’s been able to undertake several thanks to Marco Antonio’s income in New York State. The house that once had just two rooms is now much bigger, with a broad colonnade shading the patio and a white tile floor that has to be mopped constantly because of the dogs who track in mud, the tracks of Rosa’s moped, and the heavy afternoon downpours.

Rosa doesn’t worry about money. She eats when she’s hungry and sleeps when she needs to. What does cause her heartache is that the wait for Marco’s return has become very long. She misses him. Jasmin also misses him, but she trusts what her dad has told her: that he’ll return to Guatemala, and that when he does it’ll be a surprise.

“He always tells us that when he’s going to come, it’ll be all-of-a-sudden,” Jasmin said. Maybe that day, she’ll see him appear under the mango tree, see him for the first time in 10 years, and be able to embrace the man she only knows through a screen.