Translation: Rich Brown

Photography: Melissa Miranda

To get home, Yasmin Martín and Miqueas Bravo have to walk a steep, narrow path on the crest of a forested hill that forms part of the hamlet of Quince de Enero in Malacatán.

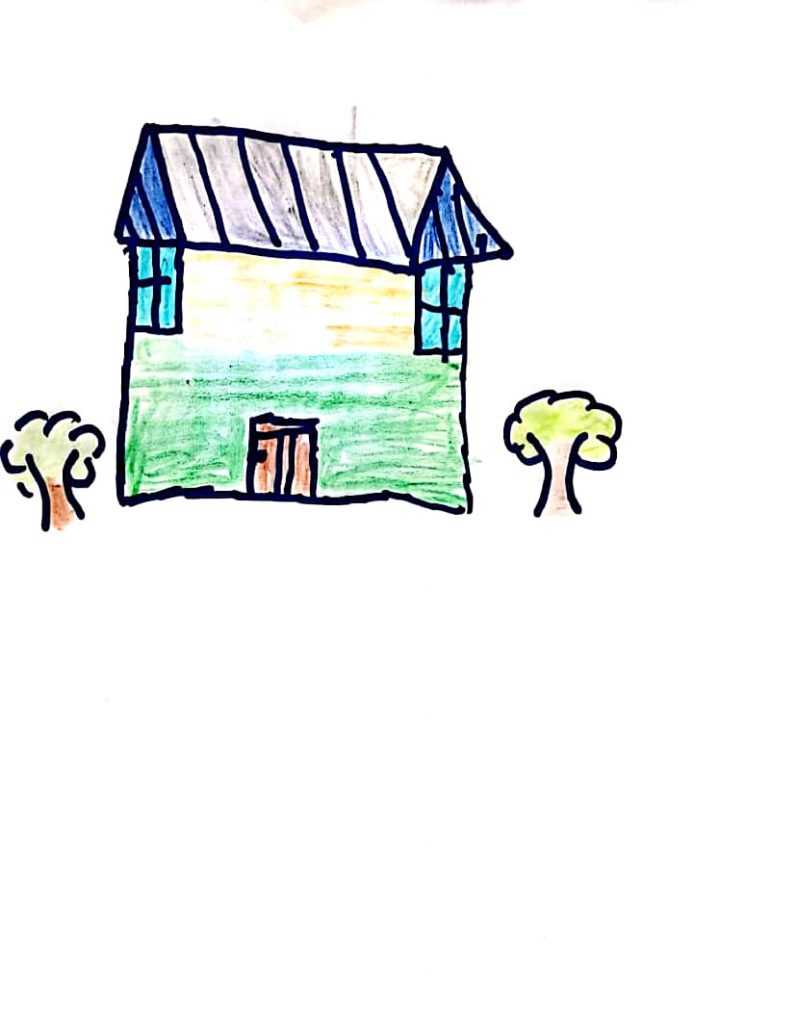

Between cousins, siblings, aunts, uncles, and grandparents, the family counts 18 members who live crowded into a one-room house with rough concrete walls, a sheet-metal roof, and a dirt floor. Beside the outhouse there’s a patio where the kids can play marbles or play with the pets. In the one big room of the house, there’s barely space to sleep. Their table can’t accommodate the whole family, so the family takes turns in groups eating around it.

It’s a house just like the others of the hamlet, except those that, thanks to remittances, have had sheet-metal replaced with concrete and dirt with tile floors.

Yasmin is the youngest of three daughters. Almost two years ago, her mother moved to Tapachula, Mexico, to work and send money to her daughters. Even though her mom travels every two or three months to see them, these sporadic visits – more frequent than those most migrants can make – aren’t enough for Yasmin.

“When I grow up, I want to help my mom so she can be in her home,” she wishes, with a voice that’s smooth but very certain about what she says. Her hope is to grow up and go to Tapachula to find a job that will let her send money to her family, especially to her mom. Her plan is to relieve her mother by herself becoming a migrant.

With their mother absent, Yasmin and her sisters are cared for by their grandmother Felipa Ramos López, 65 years old with long white hair. For different reasons, each of Felipa’s six daughters is a single mother. They’ve all had to find ways to feed their children. As Felipa says, theirs is a family of single moms.

In this family of single mothers, Yasmin isn’t the only one who is ready to leave her country. Her cousin, Yorbin Audelio Bartolón, 13 years old, has confessed to Mercy, his mom, that he wants to cross into the US to reunite with his dad and his 16-year-old brother. “My brother left out of necessity,” Yorbin says, in a timid tone.

“The only thing I don’t like about here is the work,” he jokes, once he becomes a little more confident. Every day, Yorbin has the task of chopping wood from the forest and carrying it back to the house for the family to use. Beyond that, he says he enjoys life in the hamlet a lot. Like the rest of the kids in the community, Yorbin fantasizes about getting to the other side to make his own money. He also dreams of being a soccer player and of changing his name – to anything else, because he doesn’t like his own.

Miqueas, another boy in the family, also doesn’t like his name. That’s why everyone calls him “Micky.” He does have his mom by his side, but for eight years he hasn’t heard anything from his dad. He doesn’t talk much about him. Once in a while, in conversation during meals, the story comes up of the man who set off for the US but never reappeared. Nobody knows if he made it, or if he died, or if he simply sought to abandon his family. Celia Gómez, Micky’s mom, says that only God knows if her husband is alive or dead. She was left without so much as a photo to remember him by.

As the years passed, the family resigned itself to the idea that he’d never return. Celia began to look for a way to put food on the table for her kids by working other people’s fields. Five dollars is about the most she could make from a full day of work under the hot sun. This barely covered basic food for her and the five of her kids who live under her roof.

Micky doesn’t want to work the land; he wants to be a baker. “Here we live relaxed,” he says, to explain his desire to stay in Malacatán and not follow the examples of his missing father and his older brother.

Micky’s brother migrated to work in Mexico and now is the one who, every week, takes money to his mom to support the family. Although his departure pains Celia, she also appreciates the help, because without it she couldn’t support her other kids.

Beyond the few options for work, there’s been no electricity or potable water in the area for two months. Over the last weeks, they’ve felt lucky simply for the constant rains that provide water for cooking and drinking.

Despite this situation, everyone in Malacatán knows that crossing to the other side is neither easy nor cheap. The approximate cost for someone to cross the border into Mexico amounts to around $2,000. Even if Celia worked every day for a year, from sunrise to sunset, without spending a cent on food or anything else, she couldn’t save up this amount. That’s why she hasn’t gone to the US, and why her oldest son hasn’t gone, either.

Yasmin and Micky focus not the cost to cross to the US, but on what they believe awaits them on arrival. For Yasmin, it’s a job—any kind of job—that would allow her to make money and help her mom. And for Micky, it’s a country where he could open his own bakery.

“Or maybe yes, I want to go,” Micky says after contemplating his future.